The Six Social Drivers of Male Suicide and What We Can Do About Them

- Aug 18, 2025

- 6 min read

Dr. Adam Harrison is an international expert in personal and workplace well-being and kind leadership cultures. He is a former family physician, qualified attorney-at-law, company director, charity trustee, healthcare business advisor, award-winning life, leadership, and executive coach, organisational well-being and leadership trainer, and host of the 'Inspiring Women Leaders' podcast.

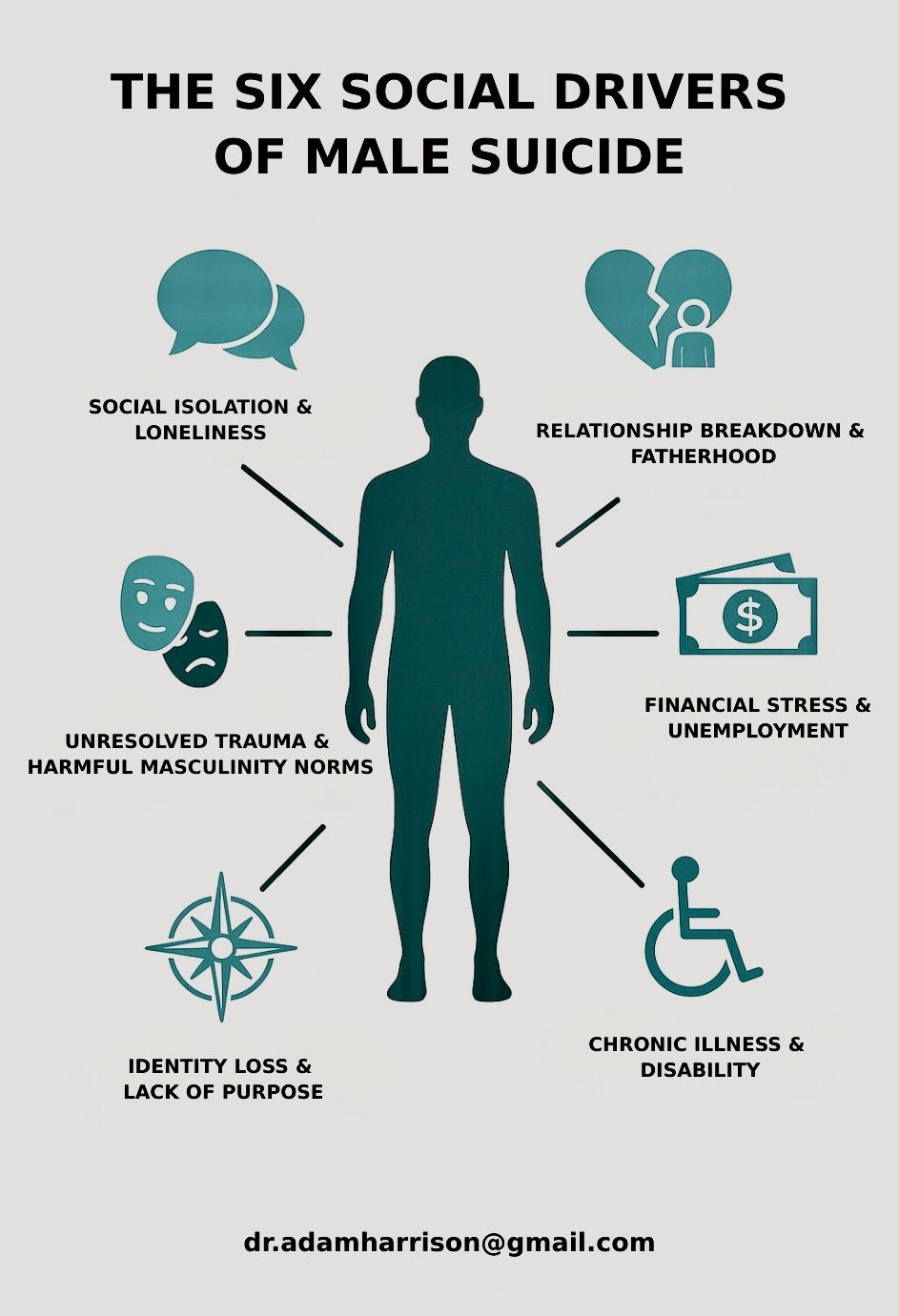

Across the globe, men are dying by suicide at far higher rates than women. While mental illness and substance misuse are important contributors, a large body of research shows that social factors (how connected we feel, our finances, our families, our roles and identities, and the societal norms we live under) often tip men from coping to crisis. This article summarises six of the most common non-medical drivers of male suicide and the practical, evidence-based solutions I use in my work.

1. Social isolation and loneliness

Why it matters:

Loneliness and weak social ties are consistently linked with suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Studies have found that social isolation elevates suicide risk, while belonging and perceived support are protective.

What helps (my approach):

Connection via an all-male community. Male-friendly spaces help lower help-seeking barriers created by stigma and harmful “I should handle this alone” beliefs.

Intra-community “tribes”. Smaller age, life event, life-stage, and interest and hobby-based groups deepen bonds.

Peer support programmes. Structured, skills-based peer support increases engagement and help-seeking.

Where this has worked:

‘Men’s Sheds’ (male-led community hubs) consistently report improved wellbeing and reduced isolation; Ireland’s ‘Sheds for Life’ showed meaningful gains in mental wellbeing over 10–12 weeks, particularly among lonelier men.

2. Relationship breakdown and fatherhood challenges

Why it matters:

Marital/relationship dissolution is one of the clearest social risk factors for men. Large registry and synthesis studies show men who are separated or divorced have markedly higher suicide risk than married men; recent reviews confirm intimate relationship breakdown is a universal risk factor for male suicidal ideation, attempts, and deaths. Loss of day-to-day contact with children can compound distress.

What helps (my approach):

Peer support for separated fathers.

Mentoring (one-to-one) helps men navigate the legal and co-parenting maze.

Parenting classes/workshops with a father-inclusive design.

Access to counselling focused on grief, conflict de-escalation, and coparenting.

Where this has worked:

Father-inclusive parenting programmes and peer-led groups can reduce parent distress and improve parenting efficacy (which often eases conflict). Randomised and quasi-experimental studies of father-focused and peer-delivered parenting support report benefits to parent mental health and family functioning.

3. Financial stress and unemployment

Why it matters:

Across economic cycles and at the individual level, unemployment and financial strain (including problem debt and housing stress) are associated with higher suicide risk. Multiple reviews and longitudinal studies show elevated risk following job loss and during recessions; financial stress is independently associated with suicidality.

What helps (my approach):

Financial literacy classes that build budgeting, debt-management, and planning skills.

Business/career coaching to restore agency and momentum.

Career mentoring to widen options and networks.

Peer support to reduce shame and increase help-seeking.

Where this has worked:

A randomised controlled trial of Building Financial Wellness improved financial capability and reduced strain, key pathways to lower psychological distress.

Individual Placement & Support (IPS) (evidence-based employment support) improves competitive employment and mental-health outcomes across diagnoses; returning to work is a powerful protective factor for many men.

Digital interventions targeting ‘money worries’ show acceptability and mental-health improvements, pointing to scalable options.

4. Unresolved trauma and harmful masculinity norms

Why it matters:

Childhood maltreatment and later trauma (including PTSD) are strongly associated with suicidal ideation, attempts, and deaths. At the same time, strong conformity to traditional masculine norms (emotional stoicism, self-reliance) is linked with lower help-seeking and greater suicide risk among men.

What helps (my approach):

Trauma-informed counselling (e.g., EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing), CPT (Cognitive Processing Therapy) / PE (Prolonged Exposure) pathways, where appropriate).

Peer-led men’s circles with clear safety boundaries and emotional-literacy practice.

Emotional-literacy workshops that normalise vulnerability and teach skills.

Positive male role-modelling through mentoring and community leadership.

Where this has worked:

Among military veterans, initiating evidence-based trauma therapies (CPT/PE) is associated with lower suicide risk versus no initiation. Reviews show that gender-sensitive services designed around men’s help-seeking barriers improve engagement and outcomes.

5. Identity loss and lack of purpose

Why it matters:

Feeling that life lacks meaning or purpose and the associated feeling of being “lost” / “stuck” is a robust correlate of suicidality. Meta-analyses (including recent work in young people) show that meaning in life is moderately and consistently protective against suicidal ideation. Retirement and other role transitions can heighten risk for some men by disrupting identity, status, and routine.

What helps (my approach):

Coaching for life transitions (retirement, redundancy, relocation) that rebuilds role, routine, and contribution.

Mentoring to reconnect strengths to service.

Peer support to replace “going it alone”.

Purpose-discovery workshops (meaning-centred approaches).

Where this has worked:

Meaning-Centered Men’s Groups for men facing retirement, improved resilienc,e and reduced suicide-risk markers in early trials. Meaning-centred interventions (including mobile formats) have reduced suicidal ideation in depressed adults, and therapies that directly target belonging and disconnection show promise.

6. Chronic illness or disability

Why it matters:

Physical health conditions, especially chronic pain and some long-term diseases, are associated with elevated suicide risk, even after accounting for mental disorders. Disability is also linked to higher suicide mortality and ideation in longitudinal and population studies. Social mechanisms (isolation, identity change, loss of function/income) are key.

What helps (my approach):

Disabled community sub-groups within a wider men’s hub to ensure accessibility and belonging.

Condition-specific, peer-led groups (e.g., pain, cancer, cardiac illness) to exchange practical strategies and reduce stigma.

Health/transitions coaching to navigate work, activit,y and identity changes.

Where this has worked:

Peer-led programmes for men with prostate cancer and other chronic conditions improve exercise adherence, self-management, and often reduce distress and isolation, mechanisms that buffer suicide risk. Evidence from randomised and systematic studies shows small-to-moderate mental-health gains and better adjustment for many participants.

Pulling it together: A male-friendly model that works

A practical illustration of the above elements at scale is ‘MATES in Construction’ (‘MATES’ = Mental Awareness Training and Education for Safety), a multimodal, peer-driven programme that has improved help-seeking, literacy, and connection in a high-risk male workforce, through on-site training, connectors, and case management. Systematic reviews and qualitative studies support its effectiveness and the importance of social identity and peer pathways in engagement.

Conclusion & Call to action

Male suicide is preventable when we tackle the social levers head-on: connection, relationships and fatherhood, financial stability and meaningful work, trauma- and masculinity-aware support, purpose, and accessible support for health/disability. The solutions above are practical, scalable, and already working in diverse settings.

If this resonates, I’d love to hear from you:

Need my help? Get in touch whether for you, a loved one, or your organisation.

Know someone who might benefit? Please share this and connect us.

Want to help my mission? “To transform men’s mental wellness and reduce the male suicide rate by creating and providing empowering spaces for connection, education, mentoring, and leadership.” Let’s partner on programmes, funding, venues, research, or referrals.

Found this useful? Kindly share it with your network to help more men find the support they deserve.

Read more from Dr. Adam Mark Harrison

Dr. Adam Mark Harrison, Leadership and Wellbeing Coach and Trainer

Dr. Adam Harrison is a leader in the fields of well-being, workplace bullying, and leadership. After experiencing burnout and being a target of workplace bullying as a junior doctor, the second stage of his career has nurtured a strong interest in coaching individuals affected by these challenges, for which he received an international award in 2024. To broaden his reach and deepen his impact, he has expanded his approach by creating and facilitating training events on topics such as personal and workplace well-being, workplace bullying, the benefits of kindness in the workplace, and 'How to be a Great Leader', in multiple countries around the globe. He is also enjoying more recent roles as a company director and trustee of a charity which aims to end adult bullying in New Zealand’s organisations.

Selected sources (concise)

Calati & Courtet (2019). Social factors and suicide risk; narrative review.

Motillon-Toudic et al. (2022). Loneliness/social isolation and suicidality; systematic review.

Øien-Ødegaard et al. (2021); King et al. (2022). Relationship breakdown and male suicide; registry/umbrella syntheses.

Milner et al.; Oyesanya et al.; CDC NVDRS analyses unemployment, financial strain and suicide risk.

Angelakis et al. (2019); PTSD, suicide reviews (2022). Childhood trauma/PTSD and suicidality.

Seidler et al. (2016); Scotti Requena et al. (2024). Masculinity norms and men’s help-seeking/suicide risk.

Guo et al. (2023); Li et al. (2024). Meaning in life as a protective factor - meta-analyses.

Heisel et al. Meaning-Centered Men’s Groups pilot outcomes.

DiBlasi et al. (2024); Kwon et al. (2023). Chronic pain/long-term conditions and suicide.

Men’s Sheds and MATES in Construction peer/community programme evaluations.