Why Do We Want Love and Fear It - The Four Emotional Patterns Formed in Childhood That Follow Us

- Brainz Magazine

- Jan 30

- 8 min read

Updated: 7 days ago

Written by Helen Jun Chen, Guest Writer

I want to feel, but my mind won’t let me. Have you ever wanted closeness, but at the same time felt afraid of it, as if it were unsafe or even dangerous?

I never understood why I held onto this belief. I knew it was wrong, but I just couldn’t let it go. Until one day, I started writing my book and found its root. That’s when I realized this wasn’t a personality flaw. It was an attachment pattern.

Even if that question doesn’t quite fit your experience, keep reading. Attachment patterns shape all of us, how we receive love, how we treat others, and how we relate in relationships. In this article, I will walk you through the four emotional attachment styles and share how I came to recognize my own. And maybe, through that lens, you’ll start to understand yours, too.

What is emotional attachment?

This theory, developed by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth, describes how people emotionally bond with and relate to others, especially in close relationships. These patterns usually form in early childhood based on how caregivers respond to a child’s emotional needs.

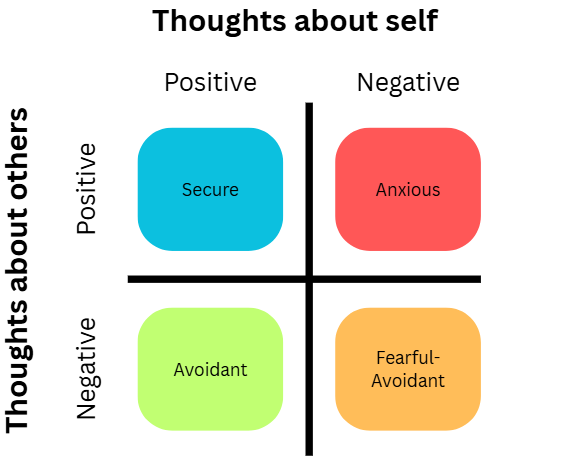

Before we go deeper, I’ll share a simple visual overview I created of the four attachment styles, so you have a clear picture of the framework we’re about to explore and how each style is formed.

At its core, children learn two unconscious beliefs:

Am I worthy of care and love?

Can I rely on others to be there for me?

Different caregiving patterns lead to different answers and, therefore, different attachment styles. So, let’s start with the four main types of attachment, and I’ll show you how each one is formed.

1. Secure attachment

Core belief: “I am worthy of love, and others can be trusted.”

This is the healthiest attachment style. People with secure attachment feel comfortable with both intimacy and independence. They can communicate needs clearly, handle conflict without panic, and trust their partner without losing their sense of self. They’re steady, supportive, and emotionally available. If you meet someone like this, you usually don’t have to guess where you stand. Their behavior is consistent.

How it forms: Secure attachment usually comes from consistent emotional safety in childhood. Caregivers are reliably responsive. The child learns:

My feelings matter

People come back

It’s safe to depend on others

My personal reflection (why this isn’t me): When I was a child, my parents were hustling, so they sent me to China to live with my grandparents. Since I have memory, I’ve already been without my parents. I stayed in China for five years, and before I reunited with my parents in Hungary at age eight, I saw them only about three times a year.

And every time they left, they left secretly, so I couldn’t protest, couldn’t hold onto them, and couldn’t even say goodbye. Each time it happened, I felt like the world was ending, like I was being abandoned all over again.

So no, I didn’t grow up with emotional safety. I didn’t grow up learning that people stay, or that love is stable. That’s why I know I’m definitely not in this category, and this attachment style hasn’t developed in me.

2. Anxious attachment

Core belief: “I’m not sure I’m enough. I might be abandoned.”

These people have a strong desire for closeness and reassurance. They are really sensitive to signs of rejection and often overthink or constantly seek validation. There is a deep fear of abandonment underneath everything. They tend to be passionate in relationships, but also emotionally clingy or overwhelmed when their needs feel unmet.

How it forms: This attachment style develops from inconsistent care in early childhood. Caregivers are sometimes loving, sometimes unavailable. Attention is unpredictable. As a child, you learn that love is not stable. It has to be earned. You start to believe that you must behave, perform, or try harder to receive care. Over time, the child learns that love is uncertain and that they have to stay alert to keep people close.

If I don’t try hard enough, I’ll be abandoned.

This belief, that love has to be earned through effort and performance, is something I’ve explored more deeply in my writing on how women often pay an invisible emotional cost for ambition.

My personal reflection: This was definitely a pattern I showed in childhood, especially the extreme clinginess. My parents would sometimes visit me, then disappear again.

That pattern taught me something early. Love is not forever. Love is uncertain.

So I tried to be good. I tried to behave. I tried to be the “good girl,” hoping that if I did everything right, my parents would come more often, stay longer, and choose me over their careers. But this changed over time. When I returned from China to Hungary at age eight and reunited with my parents, something slowly shifted. The environment changed, and so did I.

3. Avoidant attachment

Core belief: “I can only rely on myself.”

People with this attachment style tend to value independence over closeness. They feel uncomfortable with vulnerability, tend to suppress emotions, and often pull away when relationships become intense or demanding. They are emotionally distant, slow to commit, and often appear self-sufficient, even when they’re not.

How it forms: This attachment style usually develops in response to emotional unavailability in childhood. Caregivers may be distant, dismissive, or rejecting. Emotional needs are minimized by not allowing crying and discouraging the expression of feelings. Vulnerability is seen as weakness.

What the child learns: Emotions are a problem. Needing others leads to disappointment or rejection. So the safest option becomes relying only on myself.

My personal reflection: When I returned from China to Hungary at the age of eight, I thought I was finally going to receive the love from my parents that I was craving, a love that wouldn’t disappear. But my parents were still hustling. And while they were physically present this time, the house felt cold. No one was truly there emotionally. Conversations were transactional and practical, but never warm or caring.

When I struggled at school and tried to talk about it, my parents always blamed me, saying it was my fault. When I cried, I was told it was a weakness. And over time, I stopped trying to explain myself.

Slowly, I learned something painful: people cannot be depended on, and maybe closeness is something that does not even exist. So I adapted. I turned inward, and I learned to rely on myself. In adulthood, this turned into fear, fear of letting people get too close. Vulnerability started to feel unsafe.

But this still isn’t fully me. Because at the same time, I do long for closeness. Just like when I was in China, counting the days until my parents’ next visit, holding on to hope. So this isn’t the end of the story.

Let’s bring it to the next level.

4. Fearful-avoidant attachment

Core belief: “I want closeness, but it feels unsafe.”

This attachment style is a mix of anxious and avoidant traits. There is a deep desire for intimacy, paired with an equally deep fear of being hurt. It often shows up as push-pull behavior, difficulty trusting others, and relationships that feel intense but unstable, confusing for both sides.

They want closeness, but when someone gets too close, they panic. Relationships with them can feel hot and cold, a cycle of coming close, then pulling away. Their nervous system doesn’t know how to feel safe in connection. As a result, they may shut down emotionally or become reactive when vulnerability is triggered.

(That’s me.)

How it forms: This style develops from fear. It often begins when a child receives both comfort and fear from the same caregivers. The caregivers who were supposed to offer safety also created confusion, chaos, or pain. This creates a nervous system that associates love with unpredictability and danger.

What the child learns is deeply conflicting: I need closeness, but closeness is dangerous. They internalize the belief that people hurt the ones they love, and that love itself can’t be trusted. Over time, this creates deep trust issues and emotional chaos.

My personal reflection: When I was in China, love was uncertain. That made me extremely needy and clingy, always waiting for my parents’ next visit and longing for closeness. When I returned to Hungary, the opposite happened. I was emotionally neglected, and I wanted to grow up as soon as possible to escape this unbreathable environment.

My parents didn’t have a happy marriage. They shouted. They fought.

I remember the broken glasses, the flying objects, and the destroyed furniture. As a child, watching those scenes was terrifying. And then the next day, everything would be silent, as if nothing had happened. That instability made me feel unsafe around the very people I depended on. But I still wanted their love and wished for affection that never came.

So an internal conflict formed at the same time:

Closeness is something I desperately want

Closeness is something that hurts

In adulthood: I still unconsciously crave affection, the kind I never received as a child. But at the same time, I’ve learned to depend only on myself. And when someone starts to get close to me, I panic. I push them away.

Unconsciously, it’s telling me that if I let people in, they will hurt me, making attachment feel dangerous.

My mind consistently whispers to me: if I let them close, they will leave anyway, suddenly and unpredictably. Just like my parents did. Just like the fights that came out of nowhere. Just like their divorce.

Somewhere along the way, I learned to believe that people hurt the ones they love. So my mind stepped in to protect me. I learned to manage my feelings instead of feeling them. To stay guarded and to stay ahead of the pain. And eventually, I never let myself overdepend on anyone or feel too much toward them.

Recognition is the first step, but not the end

Understanding my attachment style didn’t magically fix it. I know the belief is outdated. I know not everyone leaves. But every time I try to open up, the fear from those childhood scenes comes back, so strong that I can’t move past it.

Because insight alone doesn’t calm a nervous system trained in fear. Still, recognition matters. It turns shame into understanding. It turns “what’s wrong with me?” into “this makes sense.” And that matters. Because recognition is the first step. The next is unlearning.

Real change doesn’t come from fixing ourselves, but from creating safety and capacity for growth, a shift I’ve also written about in the context of choosing growth over constant self-correction.

And you?

Which attachment style felt familiar to you? Have you started to recognize your own patterns, and if so, have you found ways to soften them?

I’m still learning. Still unlearning. But naming the pattern was the first time I stopped blaming myself and started understanding myself. This reflection emerged while I was writing my book, a longer exploration of the emotional patterns we carry and how they shape the way we move through work and life.

Connect with me

If you’d like to read more of my work, you can find it on helenjunchen.com, connect with me on Instagram (@cjhelen_), or subscribe to my newsletter for reflections on work and everyday life.

Helen Jun Chen, Guest Writer

Helen Jun Chen (pen name: CJ. Helen) is a writer and project management professional, born in Europe with Asian roots, exploring the space between external achievement and internal experience. She writes for capable professionals who are often exhausted or questioning why success doesn’t feel the way they expected. Her work blends lived experience with reflections on career development, workplace behavior, and emotional well-being, grounded in the belief that well-being is the foundation of sustainable professional success.